A simple model of decision making uses WTA (winner take all) where the option with the highest evidence takes control. The important part of WTA is the “take-all” part [Mysore and Kothari 2020]. Although the process of representing the highest evidence is well studied, the take-all part is less well studies. Vert little is known about the circuit mechanisms underlying unitary output generation [Mysore and Kothari 2020].

When choosing to turn left or right, the OT (optic tectum) in the midbrain is a central player. In mice the OT has a head-movement motor map where specific regions will turn the head left or right along the yaw, roll, or pitch axis. These output neurons are marked by the pitx2 transcription factor [Masullo et al 2019], [Choi JS et al 2021], [De Malmazet and Tripodi 2023]. Interestingly, these pitx2 head movement neurons receive essentially no visual movement, but receive multimodal input, particularly whisker input in mice [Xie Z et al 2021].

The simulated animal for this essay has only limited visual input, non-image photosensors, restricted to simple phototaxis. It does have a lateral line sense, where in fish senses surrounding water motion to detect obstacles and potential prey. Zebrafish can forage in the dark, which requires the lateral line [Carrillo and McHenry 2015], specifically the head lateral line.

Race to threshold – Mauthner cell

As a simplified example of decision making, the acoustic startle reflect and the hindbrain Mauthner cells in fish. There are two Mauthner cells in R4 (hindbrain rhombomere 4), one on each side. This startle reflex is a very fast (20ms) three-synapse circuit to escape danger. A loud sound drives acoustic sense neurons, which drives the ipsilateral Mauthner cell, which drives contralateral motor neurons to quickly turn in a “C-start” before swimming away [Bátora et al 2021]. This simple circuit is essentially a Braitenberg vehicle [Braitenberg 1984]. The Mauthner cells can also be driven by touch, vestibular, or by OT, and in zebrafish larvae, the head touch connections develop first, before the acoustic inputs [Kohashi et al 2021].

The above diagram shows the Braitenberg-like circuit of the Mauthner cell. Danger sensing neurons, acoustic, touch, or OT, drive the ipsilateral R4.mc (Mauthner cell in rhombomere 4), which drives contralateral N.mn (spinal motor neurons). This circuit, however, implicitly assumes that a danger sense will be dominated by one side or the other because it can’t compare the left and right signals.

Although touch from the animal bumping into an obstacle is often unilateral, sound is bilateral, which means the decision needs to handle some comparison between the two sides. A simple decision model is a race to threshold [Vickers 1970], but a simple race model is not optimal. Instead it is more efficient to compute differences between alternatives [Bogacz and Gurney 2007]. One of these models has two leaky accumulators with lateral inhibition [Usher and McClelland 2001]. DDM (drift diffusion) is another popular model with only a single accumulator with positive and negative inputs [Ratcliff 1978], but that system doesn’t fit this Mauthner cell circuit. In a race to threshold decision, the first accumulator to reach a threshold wins.

In the Mauthner cell circuit, the cell’s membrane voltage can serve as an accumulator and the neuron’s action potential as the threshold. The first R4.mc to reach the action potential threshold wins. The first graph below shows this race.

The above graphs show a simple race to threshold model for the Mauthner cells. The second graph shows the main issue: the firing of the winning side doesn’t prevent the losing side from also continuing to accumulate and fire. The models here are purely qualitative toy models for illustration. There is no attempt at accuracy to actual R4.mc values.

The current circuit can’t prevent the losing R4.mc from continue accumulating and firing shortly after, which might muddle the downstream motor neurons, possibly preventing a proper C-start and escape. In the actual Mauthner cell circuit, this conflict is solved by feedback inhibitory neurons that suppress the contralateral R4.mc [Koyama et al 2021]. Interestingly, this suppression is by direction electrical connectivity, not by inhibitory neurotransmitters. This feedback inhibition stop the accumulation of the contralateral R4.mc by hyper polarizing the membrane voltage directly, essentially resetting to zero.

The above diagram adds feedback neurons to suppress the losing R4.mc after an event. This suppression needs to be relatively short. The Mauthner cell only fires a brief burst, not an extended sustained output, which means the feedback inhibition only applies to the immediate event. This system may be a sufficient lockout for the highly specialized startle reflex, but a more general decision system may need a more complicated lockout system.

OT locking out for WTA

Let’s consider the OT crossed turning projection, which is used for orienting and seeking, while the OT uncrossed output is used for avoidance. OT decides to turn left or right for many input types, including visual, auditory, lateral line, touch, and even abstract cognitive decisions from cortical inputs. OT.co (OT crossed output) neurons project to R6.rs (mid-hindbrain reticula-spinal), which then projects to N.mn (spinal motoneurons) [Wheatcroft et al 2022]. This R.rs accumulation circuit exists in frog tadpoles, where they receive direct N5 (trigeminal) head touch input [Buhl et al 2015]. This circuit is roughly similar to the Mauthner cell circuit above, where OT.co replaces the sensory neurons, and the contralateral/ipsilateral crossing patterns are different.

So, let’s apply an ongoing-action lockout to the OT turning circuit by disabling OT output when an action is occurring. Unlike the specialized Mauthner cell circuit, which directly inhibited R4.mc, support the lockout suppresses the OT input to the accumulation circuit. In mammals, OT.co are inhibited by Snr (substantia nigra pars reticulata) and H.zi (zona incerta) [Doykos et al 2020]. H.zi is closely associated with movement, which suggests it could be a broad movement corollary / efference copy [Hormigo et al 2023]. H.zi appears to activate after or around movement onset, not during decision making [Hormigo et al 2023]. This timing contrasts with Snr, which drops its suppression just prior to movement. Either Snr or H.zi or a combination of the two is capable of suppressing OT.co during ongoing movement, which would eliminate input from the downstream R6.rs turning neurons.

Along with an inhibition of OT.co, H.zi also inhibits ipsilateral R6.rs chx10 turning neurons [Cregg et al 2020], but that study does not report an Snr input to R6.rs.chx10. That H.zi input could serve as a similar feedback inhibition as the Mauthner cell circuit, but the following simple model only uses the OT.co suppression.

The above chart shows a model of R6.rs turning neurons as leaky integrators for OT.co input, where the value abstractly represents the R6.rs membrane voltage. In this configuration, an action potential for turning left disables the OT input, but does not disable the R6.rs neurons directly. The OT input to R6.rs stops, and the R6.rs neurons leak back to their initial condition.

Increasing gain to avoid metastability

The R4.mc circuit is hyperoptimized for speed, including the feedback lockout circuit, which means it can lock out the loser within a short time, but even the hyper optimized circuit has limits. The Mauthner cell itself takes time to fire, and the feedback neurons also take time to fire. If the lower reaches its AP (action potential) threshold before the feedback inhibition takes hold, both R4.mc will fire, which will disrupt the animal’s escape. This issue of in-between decisions of greater for other decision circuits that aren’t as optimized as the Mauthner cell circuit. In frog tadpoles, disconnecting the midbrain impairs hindbrain decisions because of too many bilateral synchronous firing instead of limiting activation to a single side [Larbi et al 2022]. To improve the response, we need additional circuitry to distinguish the winner from the loser.

FFI (feedforward inhibition) can act as a high-pass filter, moving noise and weak signals from the accumulation in a gated accumulator model [Schall et al 2011]. Contralateral FFI could inhibit the weaker signal, increasing the division between the weaker and the stronger. But contralateral FFI works much better after the addition of lateral disinhibition [Koyama et al 2016].

The above circuit adds FFI neurons to the Mauthner cell escape circuit. A left sensory input will suppress the right Mauthner cell and vice versa. This contralateral inhibition should increase the difference between the two signals. Note, that the diagram has omitted the feedback inhibition because here we’re only interested in the ramp to threshold, not the lockout phase discussed earlier.

The above charts show several scenarios with the FFI added to the circuit. The first chart shows a plain ramp to threshold without any FFI added. The second shows the addition of weak FFI. Weak FFI increases the time difference between threshold crossing at the cost of slowing the decision slightly.

However, increasing the FFI weights further causes the system to break entirely as in the third chart. Because the two signals are nearly equal, and because the FFI is strong, the FFI ends up inhibiting both choices and the decision never reaches threshold [Koyama et al 2016]. This problem is mainly when the inputs are fairly close. As the final chart shows, if the inputs are widely separated, the large FFI inhibition still allows the winner to reach threshold. However, widely separated inputs were never the original problem.

Although this dual output suppression is a problem for the escape circuit because it seeds to make an immediate decision, it could be a benefit in a more leisurely situation where the decision should be postponed until a clear winner emerges. A good deal of decision research considers delayed response time as a measure of conflict.

But for the escape circuit, this dual suppression is a problem. Contralateral inhibition can accentuate the differences, but at the cost of squashing the result entirely. A solution is to add lateral disinhibition between the FFI neurons [Koyama et al 2016]. Only the stronger input can inhibit the contralateral choice.

The above decision circuit adds lateral disinhibition to the two FFI neurons. If the left sense is stronger, it with both inhibit the right R4.mc and disinhibit the left R4.mc by inhibiting the right FFI neuron. This should minimize the situation where nearly equal inputs inhibit both outputs.

The above chart shows the plain ramp to threshold and the FFI with disinhibition circuit for the same inputs. As the graph on the right shows, the disinhibition circuit greatly amplifies the difference between the inputs, making a clear decision.

This disinhibition pattern can also be modulated by top-down control, creating a two-phased decision [Shen B et al 2023]. Before the top-down disinhibition is activated, the two options accumulate evidence with only a minor suppression of their competitor. Enabling disinhibition quickly forces a WTA choice.

Lamprey optic tectum

While R4.mc supports a specialized escape circuit, OT supports a general orientation decision to turn left or right. As its name suggests, OT receives optical information from the retina, but in mammals it also receives whisker information, in fish it receives lateral-line information, and in lampreys and some fish it receives electrosensory information. The lateral-line and elestrosensory systems are closely related. The question immediately arises for the OT: which sense came first? Larval lampreys do not have image forming retinas, but only ocellus-like photoreceptors [Salas 2016], and the larval lamprey retinal area does not project to OT [Barandela et al 2023]. The larval OT does project to M.rs (midbrain reticulospinal, specifically nMLF – nucleus of the medial lateral fasciculus) [Barandela et al 2023], but I haven’t found any study reporting the inputs to the larval lamprey OT.

A later lamprey metamorphosis expands both the retina and the OT into image supporting systems and connects the two [Barandela et al 2023]. During that metamorphosis OT greatly expands and becomes a seven layered structure comprised of alternating white and grey layers.

In adult lampreys the retinal connects to OT.s (superficial layer of OT) and the ELL (electrosensory) connects to OT.i (intermediate layer of OT) with minimal overlap [Kardamakis et al 2016]. The output OT.co (crossed OT output neurons) extend dendrites to both OT.s and OT.i and integrate the two senses [Kardamakis et al 2016].

This essay will focus on the electrosensory path and OT.i. First, because, like the lamprey larva, the simulation animal does not have an image forming eye, but does have a lateral-line sense. Second, because the mammalian OT pitx2 turning area is also in OT.i [Masullo et al 2019], and receives whisker input but minimal or no visual input [Zahler et al 2021], [González-Rueda et al 2024]. Mexican blind cavefish show denser somatosensory in OT with increased somatosensory input [Patton et al 2010].

For OT as a decision circuit, there are two questions: how does any lateral inhibition between the left and right choice connect, and is the inhibition system feedforward like the Mauthner cell or a feedback system? For visual and auditory input, the lateral inhibition uses R.is (nucleus isthmus). In all vertebrates, R.is provides a donut-like center enhancement and surrounding inhibition [Mahajan and Mysore 2022], which includes suppressing contralateral input [Schryver 2021], but does not project contra laterally to the midbrain [Fenk et al 2023]. However, the OT.i lateral line may not use R.is. In lamprey an electrosensory distractor does not suppress a visual stimulus, it doesn’t suppress another electrosensory stimulus [Kardamakis et al 2016]. This suggests that visual and lateral line use different systems for lateral inhibition. In mammals the R.is (R.pbg parabigeminal in mammals) provides ACh to the visual OT.s layer as part of the selection process, but OT.i and OT.d (deep OT) receive ACh from Ppt (pedunculopontine tegmentum) and P.ldt (laterodorsal tegmentum) not from R.is.

The second question is whether the decision sharpening uses feedforward inhibition or feedback inhibition. The R.is circuit seems more of a feedforward inhibition system, because it inhibits based on ongoing input, not sampling from a ramping population of neurons. But the mammalian OT is a central accumulator in a decision loop involving the basal ganglia and cortex [Brody and Hanks 2015], which is only possible as a feedback loop. This feedback loop requires a ramping population of recurrently connected neurons, because an integrate-and-fire system like the Mauthner cell only fires when the final decision is made, but a feedback loop needs intermediate values. OT has recurrent connections in mammals [Basso and May 2017], [Liu Z et al 2016], frogs [Khakhalin et al 2014], [Felch et al 2015], [Jang EV et al 2016], and zebrafish OT shows edge-of-chaos spontaneous avalanche behavior, which likely also requires recurrent connectivity [Zylbertal and Bianco 2023], but I don’t know of any lamprey recurrent connectivity, or whether it exists in OT.i or OT.co. It’s possible that the feedback-based population decision system developed jawed vertebrates after the lamprey split.

The decision output should be isolated from the decision ramping process to prevent premature action. In the Mauthner cell system, the neuron itself provided that isolation because it only fires after the decision is made. But a population ramping system needs additional circuitry to isolate the decision. Like other vertebrates, the lamprey OT.co are inhibited by Snr (substantia nigra pars reticulata), which could prevent a premature decision from driving action by suppressing output while the decision is incomplete. As a parallel decision sharpening system, the lamprey midbrain dopamine system V.pt (posterior tuberculum), believed to be homologous to the mammalian Snc (substantia nigra pars compacts), receives input from OT [Suryanarayana et al 2021] nd enhances locomotor output by projections to MLR [Ryczko et al 2013], [Ryczko et al 2016], [Ryczko and Dubuc 2023] and R.rs [Ryczko et al 2020], [Ryczko and Dubuc 2023], and also projects to OT.co [Pérez-Fernández et al 2017]. In mammals Snr has a phasic increase around action onset. The V.pt DA boost amplifies and extends locomotor output. For decision sharpening, this system would invigorate the action only after the ramping process was complete or near complete while discouraging pre-decision action.

Note, the R.rs output stage can be considered its own accumulator, because the R.rs neurons themselves integrate and fire. Two-stage accumulators have advantages over a single stage [Balsdon et al 2023], [Verdonck et al 2021]. So, this system could be viewed as a two-stage accumulator system.

While the lamprey may have all the pieces to form a decision system using OT, too much is unknown about the lamprey OT to use it as the basis for the simulation. Instead, I’ll incorporate research from the mammalian OT decision system, which is much better studies, but does have the disadvantage of possibly including mammal-specific features. For example, the mammalian OT has both ramping and bursting neurons, suggesting a distinct ramping population from the OT.co output population, unlike the lamprey, which combines ramping and output in a single neuron population.

OT ramping with feedback excitation and inhibition

Consider the OT as a feedback decision system, particularly focusing in OT.i (intermediate layer of OT), because in mice a subpopulation of OT.i marked by pitx2 (a gene transcription factor) turns the head in the yaw, roll, and pitch axes [Liu X et al 2022]. Because the essay animal is fish-like with no neck, and also two dimensional, we can focus on the left-right yaw. This left-right decision is also important singe the bilateral organization of the brain means the left-right circuits are distinct from any unilateral decision, because they require commissural connections.

The mammalian OT has both ramping neurons and bursting neurons [Basso and May 2017], although the exact circuitry is not known. OT.ramp may project to burst neurons such as OT.co that send the action. For this model I’ll assume that the ramping neurons are a subpopulation distinct from the bursting and that OT.co are the bursting neurons, but this assumption is not based on any research I can find.

After a decision commits, the system needs to lockout further decisions until the new action completes. As discussed above, this lockout function is compatible with the known Snr and H.zi suppression of OT.co [Comoli et al 2012]. This lockout function is speculative because I haven’t found research about lockout for OT decisions.

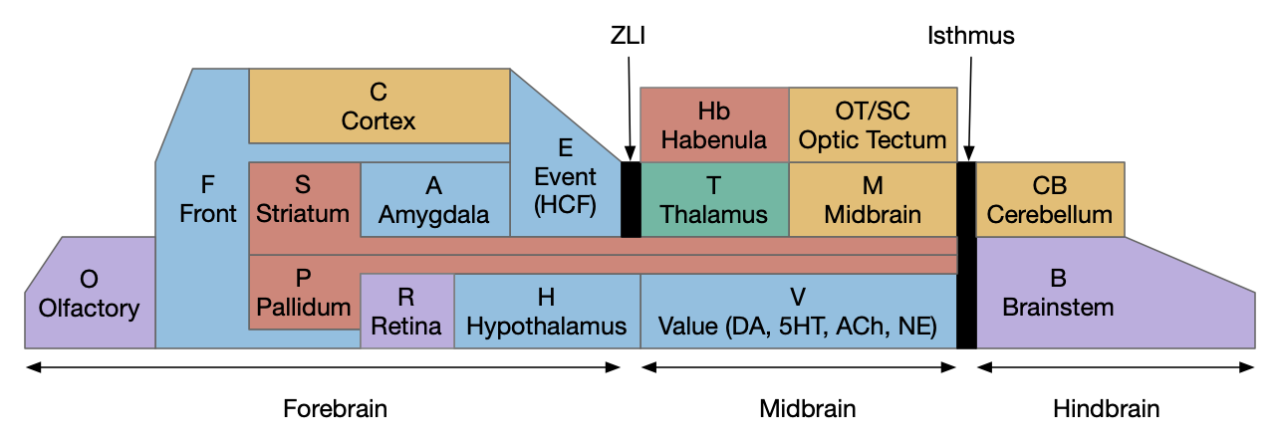

The above diagram shows the OT decision circuit. In general, OT.input is very flexible and can include abstract input from the cortex in mammals [Thomas et al 2023], as part of the cortex decision circuit. The OT.i.pitx2 neurons for mouse head turning have strong whisker input from N5 (trigeminal cranial nerve), but weak or no visual input [Xie Z et al 2021]. Although this whisker primary and the OT.i.pitx2 head turning could be a novel mammal system, the fish lateral line serves a similar function as mammal whiskers. Zebrafish larvae, for example, can learn to hunt in darkness using the lateral line, despite being primarily visual hunters [Whestphal and O’Malley 2013]. A proto-vertebrate with lateral-line sensors but without an image-forming retina could use this mammalian OT.i.pitx2 circuit for decisions. The OT accumulation and delay sustain are primarily OT.i [Basso et al 2021].

The LCA (leaky competing accumulator) model of decision making [Usher and McClelland 2001], uses a pair of leaky accumulators with feedback lateral inhibition. That model, like other decision models such as DDM (drift-diffusion), are intended to describe higher level decision making, such as modeling human tasks, but the structure is inspired by neural circuits like the OT decision system.

The OT.ramp are likely a population of recurrently connected neurons, unlike the paired Mauthner cell which integrated with its membrane potential and only fired a single AP once the threshold was crossed. OT.ramp are likely to use both membrane integration and recurrent connectivity for their ramping. For simplicity, I’m trading OT.ramp neurons as leaky integrators, which does obscure important details about the firing model, including issues with E/I (excitation/inhibition) balance and edge-of-chaos positive feedback behavior. Because OT.ramp fire during the integration, unlike Mauthner cells, the competition between left and right can use feedback inhibition instead of relying on contralateral, disinhibiting feedforward inhibition.

The above diagram shows two styles of feedback inhibition: inhibiting the OT.ramp neuron soma directly and inhibiting the OT.ramp input by inhibiting their dendrites. The soma inhibition could also include axon output inhibition. In the cortex SST (somatostatin) interneurons inhibit dendrites, PV (parvalbumin) interneurons inhibit the soma directly, and CCK interneurons inhibit the axon output. PV neurons may not be unique in inhibiting the soma, and the PV role in the cortex is more about E/I balance than lateral inhibition. However, OT neurons and cortex neurons are not developmentally related: all OT neurons derive from OT progenitors [Cheung et al 2024]. The analogy with the cortex is only to illustrate that different inhibitory neurons can target specific areas of the target neuron, and specifically introduce the ability to inhibit input to the neuron.

Let’s take a toy model of OT.ramp, as if they were a single leaky integrator for each side. Unlike real neuron population spiking, these model OT.ramp produce continuous output, which the feedback neurons can use. The purpose is to get a qualitative idea of how FBI (feedback inhibition) might work for soma-targeted inhibition and dendrite-targeted inhibition.

The above graphs show the leaky integrator OT.ramp with either no FBI, soma-only FBI, dendrite-only FBI, and both soma and dendrite FBI. Unlike the Mauthner cell FFI, the dendrite input FBI does not drive both OT.ramp to zero, which likely means that the FFI disinhibition circuit is less important. Also, unlike the Mauthner cell simulation, which measured the membrane voltage, the graphed value is a general excitation level.

The above graphs show the behavior with variations in FBI strength. The weak FBI shows a significant difference between soma-only and dendrite-only inhibition. Weak soma FBI allows both options to fire, while the weak dendrite FBI clearly distinguishes between the options. Both strong FBI circuits distinguish their outputs.

In the real recurrent neural system, output spikes are not a continuous functions, and the population may be too small to use population encoding to approximate continuity. The input itself isn’t continuous, and includes noise. In addition, recurrent excitation is a positive feedback system, and in combination with normalizing inhibition, can produce chaotic transitions between states. This model does not support edge-of-chaos behavior, which may be important to the actual system. It also doesn’t include detailed timing and oscillatory behavior, and OT is known to produce gamma (25-100Hz) oscillations, and oscillations can interact with feedback, such as for SST neurons in the postsubigulum head direction system [Simonnet et al 2017]. All of these limitations may mean that cases such as the strong FBI or the weak FBI graphs above are physically impossible.

OT feedback commissures

The left/right decision requires contralateral communication, which is relatively rare, and can help isolate some of the decision circuitry. The OT.ramp decision model above required contralateral inhibition, which means commissural feedback paths between the OT sides are particularly important. There are three main contralateral paths in the OT that I’ve found studies for:

- Direct OT to OT contralateral connections [Doykos et al 2020].

- R.is (nucleus isthmus) contralateral inhibition in some species [Gambrill et al 2016].

- Contralateral Snr and Ppt.a (anterior pedunculopontine tegmentum) inhibition, either related to the Sprague effect [Durmer and Rosenquist 2001], or as part of the basal ganglia output [Jiang H et al 2003].

The lamprey has OT input from the contralateral OT, and bilateral M.rf (midbrain reticular formation) [de Arriba and Pombal 2007], which likely includes Snr. The Lamprey OT.co has input from Snr [Kardamakis et al 2015]. Because “midbrain reticular formation” is so broad, these two studies may not contradict each other. The majority of contralateral OT projections is from OT.i with some from OT.s and OT.pv (periventricular aka deep) and more from OT.l than OT.m [de Arriba and Pombal 2007], which could correspond to the mammalian OT.i pitx2 group.

The direct OT to OT connectivity is the simplest for this circuit. OT.i to contralateral OT.i exists in the anterior OT [Doykos et al 2020]. OT.burst have projections to the contralateral OT [Basso and May 2017]. OT to contralateral OT exists for deeper OT.s and deeper of OT.id [Broersen et al 2025]. In lamprey, the majority of OT to contralateral OT is OT.i [de Arriba and Pombal 2007]. OT contralateral projections include competitive inhibition for choice, and OT contralateral projections reflect choice earlier than other decision brain regions [Essig et al 2020]. OT to OT is generally restricted to anterior OT, and about 50% of OT to OT are excitatory and 50% are inhibitory.

R.is is critical for visual and auditory competitive choice between targets on a single hemisphere [Kawakami et al 2021]. Disabling R.is.mc (magnocellular R.is) in owls abolishes all competitive OT in a single hemisphere, but that study did not examine contralateral effects [Mysore and Knudsen 2013]. In pigeons, disabling R.is.mc reduces inhibition of R.is.pc (parvocellular R.is) [Marín et al 2007], but again this study was unilateral and did not examine effects on the contralateral OT. In bearded dragons, R.is.mc is required for bilateral competition during REM sleep, but in those animals it does not project to the contralateral midbrain [Fenk et al 2023], which would include OT. The primate R.pbg (parabigeminal), which is the mammal homolog of R.is, does project to the contralateral OT [Deichler et al 2020], but the mammal R.pbg is connected with OT.s (superficial OT) visual lateral particular for ACh (acetylcholine), while OT.id (intermediate and deep OT) receives ACh from Ppt and P.ldt (laterodorsal tegmentum) [Krauzlis et al 2023], [Wolf et al 2015]. I haven’t found a study specifically examining contralateral inhibition from R.is, and while some species do have contralateral connectivity, it doesn’t appear to be directly used for the orienting/head turning decisions for this essay.

OT.i receives contralateral inhibition from a portion of Snr, particularly Snr.al (anterolateral Snr) [Jiang H et al 2003], [Velero-Cabré et al 2020], although most (75%) of Snr inhibition of OT is ipsilateral [Jiang H et al 2003]. Ppt.a and Snr are important for the Sprague effect, where inhibition of unilateral C.vis (visual cortex) input to OT results in hemispheric attentional neglect, but is restored when Ppt.a and/or contralateral Snr projections are also inhibited [Krauzlis et al 2023]. Most Snr.l projections are modulatory and depend on movement direction and modulate choice, and find little evidence for strong Snr suppression of OT.id [Doykos et al 2025], but note that this study specifically examines Snr.dl, but Snr.vm also projects to OT and has a different progenitor origin and functionality. For mice licking tasks, which use OT.l, the Snr to OT.l projection is important for licking accuracy [Lee J and Sabatini 2021]. OT.i.pitx2 projections include Snr [Masullo et al 2019].

There are OT.id projections to Ppt [Coizet et al 2009], [Melleu and Canteras 2024], [Leiras et al 2022], [Tubert et al 2019], major input from OT to Ppt GABA and ACh neurons [Morgenstern and Esposito 2024], and OT.id bidirectional connectivity with Ppt [Comoli et al 2012], [Krauzlis et al 2013], [Melleu and Canteras 2024], [Wu and Zhang 2023]. Ppt correlates with orienting of eyes, body, and limbs [Wolf et al 2015]. In contrast with studies consistently reporting OT projections to Ppt, only a few studies report any direct projections to Snr, but does include a report of OT.i.pitx2 to Snr [Masullo et al 2019]. Note, however, that Snr.p and Ppt.a are contiguous, and Ppt.a GABA can be seen as a continuation of Snr [Mena-Segovia et al 2009], and Ppt is somewhat arbitrarily defined by the location of its ACh neurons [Mena-Segovia et al 2009], which may not precisely define the limits of its glutamate and GABA neurons.

The OT projection through Ppt to Snr could participate in the inhibitory feedback loop, or implement parts of it. Snr, Ppt and the basal ganglia can affect or even determine OT decisions. This modulation could be added to an existing OT decision circuit that only uses OT to OT commissural projections for feedback inhibition, or it could be part of the original feedback inhibition.

ACh sharpening the decision output

The mammalian division between OT.ramp and OT.burst demonstrates an important issue with decisions: downstream areas should see the results of the decision, not the intermediate ramping process leading up to the decision. Mammalian decisions appears to use systems outside of OT like Ppt and Snr to produce sharp, cleanly defined bursts. How might an evolutionary progression for a proto-vertebrate decision sharpening progress, specifically to isolate downstream R.rs from the ramping process?

One potential method is to amplify the output when a decision is made. R.is.pc (parvocellular R.is) is a distinct R.is nucleus with ACh feedback projections to OT. Like the rest of R.is, R.is.pc is a short feedback loop with OT, but unlike the negative feedback in the WTA system, this is positive feedback. In birds an OT projection to T.nr (thalamus nucleus rotundus) requires ACh input to burst. Without the ACh amplification, the OT signal is too weak to drive T.nr [Basso et al 2021].

The mammalian OT.i.pitx2 turning region receives ACh from Ppt and P.ldt. The mammalian R.pbg is considered homologous to the first and bird R.is, but mammalian R.pbg ACh appears to be specific to the OT.s visual layers [Krauzlis et al 2013]. R.pb and Ppt/P.ldt are sibling neural areas, produced by the same progenitor pool in R1 at different development times [Volkman et al 2010]. Unfortunately, although R.is is well-studied for fish and bits, Ppt is not, so I don’t know if the mammalian Ppt/P.ldt ACh projection to OT orientation neurons is ancestral but simplified in fish and birds, or if the R.is ACh is ancestral and the Ppt/P.ldt ACh is a mammalian adaptation. OT varies widely among species because it’s a major visual system under strong evolutionary pressure. Even considering the basic layering, the lamprey OT has 7 layers [Basso et al 2021], the mammalian OT has 6 layers, the bird OT has 15 layers [Basso et al 2021], and the first OT is divided into paraventricular soma and a large neuropil layer, where the neuropil itself can be divided into layers. Because the essays have uses the non-visual-first model of OT evolution, I’ll use the mammalian model as ancestral and R.is/R.pbg as later refinements after image-forming vision developed.

In the above model, Ppt acts as a high-pass filter. A distinct OT ramping population produces a non-choice-selective measure of the decision progress [Horwitz and Newsome 1999], which projects weakly to Ppt. This model uses individually weak projections from OT.ramp are insufficient to drive Ppt ACh until they are collectively and possibly synchronously active. Only higher level input will drive ACh, when then boosts OT.co output and enabling boosting. The OT.id threat-avoidance system uses a similar architecture of individually weak and unreliable projections that require simultaneous activation to drive threat escape to M.pag.d (dorsal periaqueductal grey) [Evans et al 2018]. The OT.co turning system might use a similar circuit with Ppt. Note also that Ppt intrinsically produces gamma oscillations [Garcia-Rill et al 2018], which could synchronize output neurons, providing a stronger burst. Ppt could enhance OT.co bursting not only from ACh release, but also by entraining gamma oscillations in OT.

H.stn sharpening decisions by inhibiting OT.co

Another method for sharpening the R.rs decision signal is disabling the OT.co output while a decision is in progress. In larval zebrafish, swimming occurs in bouts of about 500ms, primate saccades are carefully timed around 200ms, and in rodents, stimulating OT produces step-like saccade-like head movements at around 350ms, instead of a continuous turning motion [Masullo et al 2019]. This saccade-like process around 200ms to 350ms suggests a gating system, either internally or externally driven.

As mentioned in the lockout discussion, Snr and H.zi are responsible for OT.co inhibition [Doykos et al 2020]. At the onset of primary saccades, tonic Snr suppression pauses to allow OT bursting. Snr itself is driven by H.stn (subthalamic nucleus), which itself is driven by OT [Al Tanner et al 2023], [Ricci et al 2024]. H.stn is also driven by Ppt [Al Tanner et al 2023], which is strongly interconnected by OT. When OT is activated, it can increase H.stn tonic firing from 27Hz to 45Hz [Coizet et al 2009]. Interestingly, bursting input to H.stn can produce long-lasting H.stn output over several hundred milliseconds [Ammari et al 2010]. Putting this together, OT.ramp could use H.stn to inhibit its OT.co output while the decision is in progression, possibly using H.stn as a 200ms to 300ms timing mechanism as an initial internal-only ramping period.

The above diagram shows the basic flow. When a decision starts, OT.ramp signals H.sth, which inhibits OT.co using Snr. Note that this diagram is primarily for a proto-vertebrate, although these connections exist in mammals. In mammals, the full circuit would include the rest of the basal ganglia and the cortex.

Wei W et al propose a sharpening function for H.stn using the full basal ganglia to sharpen cortical decisions [Wei W et al 2015]. In their model, ramping input to S.d (dorsal striatum) suppresses spontaneous P.d (external globus pallidus) activity, which increases H.stn, which then cancels out the primary S.d1 (striatum projection neuron with D1 dopamine receptor) to Snr disinhibition. Because P.d can only be suppressed to zero, the H.stn suppression of the decision is also limited, and eventually the decision ramp overcomes the suppression [Wei W et al 2015].

The above diagram shows a reinterpretation of the Wei W et al sharpening model, with their cortex focus replace by this essay’s OT focus. The oppositional paths of S.d1 (striatum projection neuron with D1.s dopamine receptor) and S.d2 (striatum projection neuron with D1.i dopamine receptor) prevent the OT.co output from firing while the decision is in progress. Because the S.d2 indirect path is limited by P.d, which can only be inhibited to zero, it eventually saturates, and limits H.stn activity, allowing the S.d1 path to continue increasing and eventually overcome the H.stn inhibition. This model is compatible with the view of H.stn as a decision slowing circuit during conflict [Frank 2006].

H.stn neuron activity is diverse with some studies showing at least three clusters of decision-related responses [Branam et al 2024], one of which is compatible with the Wei W et al model. This cluster of H.stn responses shows an early, sharp rise during the initial stimulus with a gradual decline until action onset.

Dopamine for sharpening and sustaining decisions

Midbrain dopamin in Snc (substantia nigra pars compacta) may play a role in further sharpening and sustaining the decision. Vertebrates have a descending Snc DA projection to MLR (midbrain locomotor region) for lamprey [Ryczko et al 2013], [Grätsch 2018], [Beauséjour et al 2025], salamander and rat [Ryczko et al 2016] and R.rs for lamprey [Ryczko and Dubuc 2017], [Beauséjour et al 2024], which enhances locomotor vigor [Ryczko et al 2016], [Ryczko and Dubuc 2017], [Grätsch 2018]. In lamprey, this descending DA projection outnumbers ascending projections to the basal ganglia by eleven to one [Ryczko et al 2013]. In zebrafish larvae, the basal ganglia primarily receives DA from local forebrain dopamine regions with either minimal or no V.da (midbrain dopamine) input [Rimmer 2020]. For a proto-vertebrate, it seems reasonable to focus on the descending DA projection instead of the smaller ascending one to the basal ganglia.

In lamprey, salient input from OT projects to V.pt (posterior tuberculum) DA neurons, considered an Snc homolog [Suryanarayana et al 2022]. V.pt DA projects to R.rs [Beauséjour et al 2024], and OT also receives V.pt input [de Arriba and Pombal 2007]. These projections enhance the activity of the downstream neurons.

In the context of decision sharpening, DA activity around movement onset would activate downstream action activity, distinguishing that action from the pre-decision ramping time.

In mammals, OT projects both to Snc [Huang M et al 2021], [Masullo et al 2019] and to the contralateral V.rmtg (rostromedial tegmentum) [Pradel et al 2021], [Guillamón-Vivancos et al 2024], which inhibits Snc. These projections collectively support turning, but not increase locomotion, place preference, or learning [Poisson et al 2024].

The above diagram has been organized to emphasize its similarity to the Mauthner cell FFI decision circuit. In the Mauthner cell circuit with contralateral FFI, a simultaneous left and right input would suppress both outputs. For that escape circuit, this dual suppression was bad because it suppressed escape, but for DA decision sharpening, the dual suppression is perfect because it inhibits partial decisions. As long as the left and right accumulators are active, the contralateral FFI circuit suppresses DA output. When one choice decisively wins, the output is disinhibited and quickly reports the decision.

The above graph shows the time course of the decision. The amber DA choice is suppressed while the left and right accumulators are in conflict. Once the conflict resolves, the DA quickly rises. In this simulation, the FFI contralateral suppression is 2:1, so the DA is release once the winner is twice the loser. The unshackled DA will now enhanced the downstream turning R.rs, committing the decision.

The V.da neurons here are the non-food-related motor DA in Snc.v, marked by aldh1a1 in mammals, and likely the specific subgroup marked by anx1a. Broadly speaking, V.da can be split into three groups: and eating and food seeking group, an action-only group, and a threat and avoidance group. An Snc.v group (aldh1a1 /anxa1) which produces movement, but does not respond to food or produce food conditioning [Seiler et al 2024], [Azcorra et al 2023], [Hadjas et al 2025]. It seems likely that the OT projection to Snc.v would be to this aldh1a1/anxa1 group, but I don’t have a paper that shows that specific connection.

Simulation

The simulations added a simple electrosense for food, which produces left and right signals depending on the heading with some noise. When the simulated animal heads directly toward the food, the left and right inputs have equal values. When the food is to one side, the closer side has a stronger signal.

Although the simulation itself didn’t produce anything particularly interesting, it did raise two larger questions about the decision making. First, whether the 2AFC (two alternative forced choice) model makes any sense at all for this evolutionary stage. Second, more questions about timing, particularly with rapid movements, and aborted choices.

2AFC (two alternative forced choice)

2AFC is a popular experiment for studying decision making. Typically, the experiment has a central cue: sound, visual, tactile (whisker), or odor for mice, and the mice must move to a left or right door port to get food, or lick to a left or right spout to water. In primate experiments, a monkey might see drifting dot patterns and must saccade to a left or right target to signal if the drift is more to the left or to the right. In these experiments, two nearly equal cues still produce a strong left or right action.

But in the electrosense simulation, two nearly equal left and right inputs would generally mean the food is straight ahead. If the food is straight ahead, the animal should make smaller turns to center the turn, not side decision-like turns. The OT is organized to make this kind of adjustment decision. Turning in the anterior OT are smaller than the wide turns in the posterior OT, and the anterior OT shows more activity as the animal moves toward the target [Essig and Felsen 2021].

If two food sources were equally distance from the animal, or their signal/distance matched, a left or right choice would be better than moving straight, but that situation would be metastable and likely resolve itself without additional decision circuitry. If the animal drifted to one side by chance, one food source would be nearer, and the animal would approach it.

Obviously, mammals have the ability to make two 2AFC decisions, but it’s not clear when that ability would be an evolutionary advantage for simpler animals. The 2AFC experiments are artificial cued situations that don’t resemble natural foraging. Although mammals can solve these situations, it seems more likely this is a byproduct of advantages aimed at a more direction situation, but generalized enough to cover the odd experiment.

Some decision researchers argue that real world options are generally sequential [Ballesta and Pado-Shioppa 2019]. Some argue that sequential decisions contrast the current option with the background, as opposed to drift-diffusion with two opposing actions, and contrast tug of war models vs sequential models [Kacelnik et al 2012]. Pure 2AFC is rare in nature [Ellerby 2028]. Reality includes competition with rivals and the potential for resources to accumulate and deplete.

Dynamic environment and slow accumulation

The second issue the simulation raised was when the animal’s situation changed more quickly than the accumulator. The dynamic environment produces obsolete partial data [Piet et al 2018]. In the simulation, the underlying non-decision behavior is a random walk. The new decision system overrides the random walk when it has a result, but the random walk does not stop for the decision. So, the random walk can turn sharply and reverse the left and right accumulators. If the accumulators are sufficiently slow, or insufficiently leaky, the partial results are now a mixture of invalid data from the past and new valid data.

There are a few immediate improvements. Shortening the accumulation or increasing the leak would shorten the timescale to minimize corruption. In mice, the midbrain accumulation timescale appears to have a τ=250ms delay time with longer integration requiring the cortex [Khilkevich et al 2024]. Rats can dynamically change the integration timescale when the environment becomes more unreliable [Piet et al 2018].

In theory, the animal could avoid making movements while it’s deciding to avoid corrupting the data, such as pausing random-walk turns by disabling the ARTR (anterior hindbrain turning region) in zebrafish. But this doesn’t seem to be a general solution because the animal would be continually pausing as it’s making a decision.

Another solution could reset the accumulators at any action, including non-decision actions like the random walk. The OT.s visual system does have a reset using V.lc (locus coeruleus) Ne (norepinephrine) to OT astrocytes [Uribe-Arias et al 2023], as a response to an escape action. In the cortex, movement preparation collapses at movement onset for that decision as a reset [Khilkevich et al 2024].

Animals rarely miss choices [Lu W and Wan X 2025], possibly suggesting an urgency signal [Cisek et al 2009], [Thura et al 2012]. An efference copy from the random walk ARTR, or a shared efference copy from the swimming CPG might force the turn decision circuit to curtail its evidence accumulation to make a decision before the random walk.

But again, I don’t know if these are general solutions. Research experiments generally work to reduce dynamic activity, such as head-fixed mice, or reporting neural activity after the animal has overtrained to produce stereotyped behavior, and introducing delays to separate neural signals to better distinguish which brain areas are active in each time period of a decision. But those necessary simplifications also erase any measurement of how the decision systems deal with dynamism [Gordon et al 2021]. Some research in auditory streaming does support dynamic decision making [Cao R et al 2021], although that study is for the cortex, and it’s unclear if those results apply to OT.

References

Al Tannir, R., Pautrat, A., Baufreton, J., Overton, P.G. and Coizet, V., 2023. The subthalamic nucleus: a hub for sensory control via short three-lateral loop connections with the brainstem?. Current Neuropharmacology, 21(1), pp.22-30.

Ammari R, Lopez C, Bioulac B, Garcia L, Hammond C. Subthalamic nucleus evokes similar long lasting glutamatergic excitations in pallidal, entopeduncular and nigral neurons in the basal ganglia slice. Neuroscience. 2010 Mar 31;166(3):808-18.

Azcorra M, Gaertner Z, Davidson C, He Q, Kim H, Nagappan S, Hayes CK, Ramakrishnan C, Fenno L, Kim YS, Deisseroth K, Longnecker R, Awatramani R, Dombeck DA. Unique functional responses differentially map onto genetic subtypes of dopamine neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2023 Oct;26(10):1762-1774.

Ballesta S, Padoa-Schioppa C. Economic Decisions through Circuit Inhibition. Curr Biol. 2019 Nov 18;29(22):3814-3824.e5.

Balsdon, T., Verdonck, S., Loossens, T. and Philiastides, M.G., 2023. Secondary motor integration as a final arbiter in sensorimotor decision-making. PLoS Biology, 21(7), p.e3002200.

Barandela M, Núñez-González C, Suzuki DG, Jiménez-López C, Pombal MA, Pérez-Fernández J. Unravelling the functional development of vertebrate pathways controlling gaze. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023 Oct 26;11:1298486.

Basso MA, May PJ. Circuits for Action and Cognition: A View from the Superior Colliculus. Annu Rev Vis Sci. 2017 Sep 15;3:197-226.

Basso MA, Bickford ME, Cang J. Unraveling circuits of visual perception and cognition through the superior colliculus. Neuron. 2021 Mar 17;109(6):918-937.

Bátora D, Zsigmond Á, Lőrincz IZ, Szegvári G, Varga M, Málnási-Csizmadia A. Subcellular Dissection of a Simple Neural Circuit: Functional Domains of the Mauthner-Cell During Habituation. Front Neural Circuits. 2021 Mar 22;15:648487.

Beauséjour PA, Veilleux JC, Condamine S, Zielinski BS, Dubuc R. Olfactory Projections to Locomotor Control Centers in the Sea Lamprey. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Aug 29;25(17):9370.

Beauséjour, P.A., Zielinski, B.S. and Dubuc, R., 2025. Behavioral, Endocrine, and Neuronal Responses to Odors in Lampreys. Animals, 15(14), p.2012.

Bogacz, Rafal, and Kevin Gurney. The basal ganglia and cortex implement optimal decision making between alternative actions. Neural computation 19.2 (2007): 442-477.

Braitenberg, V., 1986. Vehicles: Experiments in synthetic psychology. MIT press.

Branam, K., Gold, J.I. and Ding, L., 2024. The subthalamic nucleus contributes causally to perceptual decision-making in monkeys. Elife, 13, p.RP98345.

Broersen, R., Thompson, G., Thomas, F. and Stuart, G.J., 2025. Binocular processing facilitates escape behavior through multiple pathways to the superior colliculus. Current Biology, 35(6), pp.1242-1257.

Brody CD, Hanks TD. Neural underpinnings of the evidence accumulator. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2016 Apr;37:149-157.

Buhl E, Soffe SR, Roberts A. Sensory initiation of a co-ordinated motor response: synaptic excitation underlying simple decision-making. J Physiol. 2015 Oct 1;593(19):4423-37.

Cao R, Pastukhov A, Aleshin S, Mattia M, Braun J. Binocular rivalry reveals an out-of-equilibrium neural dynamics suited for decision-making. Elife. 2021 Aug 9;10:e61581.

Carrillo, A. and McHenry, M.J., 2016. Zebrafish learn to forage in the dark. Journal of Experimental Biology, 219(4), pp.582-589.

Cheung, G., Pauler, F.M., Koppensteiner, P., Krausgruber, T., Streicher, C., Schrammel, M., Gutmann-Özgen, N., Ivec, A.E., Bock, C., Shigemoto, R. and Hippenmeyer, S., 2024. Multipotent progenitors instruct ontogeny of the superior colliculus. Neuron, 112(2), pp.230-246.

Choi JS, Ayupe AC, Beckedorff F, Catanuto P, McCartan R, Levay K, Park KK. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing of developing superior colliculus identifies neuronal diversity and candidate mediators of circuit assembly. Cell Rep. 2023 Sep 26;42(9):113037.

Cisek P, Puskas GA, El-Murr S. Decisions in changing conditions: the urgency-gating model. J Neurosci. 2009 Sep 16;29(37):11560-71.

Coizet V, Graham JH, Moss J, Bolam JP, Savasta M, McHaffie JG, Redgrave P, Overton PG. Short-latency visual input to the subthalamic nucleus is provided by the midbrain superior colliculus. J Neurosci. 2009 Apr 29;29(17):5701-9.

Comoli, E., Das Neves Favaro, P., Vautrelle, N., Leriche, M., Overton, P. G., & Redgrave, P. (2012). Segregated anatomical input to sub-regions of the rodent superior colliculus associated with approach and defense. Frontiers in neuroanatomy, 6, 9.

Cregg JM, Leiras R, Montalant A, Wanken P, Wickersham IR, Kiehn O. Brainstem neurons that command mammalian locomotor asymmetries. Nat Neurosci. 2020 Jun;23(6):730-740.

de Arriba María del C, Pombal MA. Afferent connections of the optic tectum in lampreys: an experimental study. Brain Behav Evol. 2007;69(1):37-68.

de Malmazet D, Tripodi M. Collicular circuits supporting the perceptual, motor and cognitive demands of ethological environments. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2023 Oct;82:102773.

Deichler A, Carrasco D, Lopez-Jury L, Vega-Zuniga T, Márquez N, Mpodozis J, Marín GJ. A specialized reciprocal connectivity suggests a link between the mechanisms by which the superior colliculus and parabigeminal nucleus produce defensive behaviors in rodents. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 1;10(1):16220.

Doykos TK, Gilmer JI, Person AL, Felsen G. Monosynaptic inputs to specific cell types of the intermediate and deep layers of the superior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 2020 Sep 1;528(13):2254-2268.

Durmer JS, Rosenquist AC. Ibotenic acid lesions in the pedunculopontine region result in recovery of visual orienting in the hemianopic cat. Neuroscience. 2001;106(4):765-81.

Ellerby, Z.W., 2018. A combined behavioural and electrophysiological examination of the faulty foraging theory of probability matching (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nottingham).

Essig J, Felsen G. Functional coupling between target selection and acquisition in the superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 2021 Nov 1;126(5):1524-1535.

Essig J, Hunt JB, Felsen G. Inhibitory neurons in the superior colliculus mediate selection of spatially-directed movements. Commun Biol. 2021 Jun 11;4(1):719.

Evans DA, Stempel AV, Vale R, Ruehle S, Lefler Y, Branco T. A synaptic threshold mechanism for computing escape decisions. Nature. 2018 Jun;558(7711):590-594.

Felch DL, Khakhalin AS, Aizenman CD. Multisensory integration in the developing tectum is constrained by the balance of excitation and inhibition. Elife. 2016 May 24;5:e15600.

Fenk, L.A., Riquelme, J.L. and Laurent, G., 2023. Interhemispheric competition during sleep. Nature, 616(7956), pp.312-318.

Fernandes, A.M., Mearns, D.S., Donovan, J.C., Larsch, J., Helmbrecht, T.O., Kölsch, Y., Laurell, E., Kawakami, K., Dal Maschio, M. and Baier, H., 2021. Neural circuitry for stimulus selection in the zebrafish visual system. Neuron, 109(5), pp.805-822.

Frank, Michael J. Hold your horses: a dynamic computational role for the subthalamic nucleus in decision making. Neural networks 19.8 (2006): 1120-1136.

Gambrill AC, Faulkner R, Cline HT. Experience-dependent plasticity of excitatory and inhibitory intertectal inputs in Xenopus tadpoles. J Neurophysiol. 2016 Nov;116(5):2281-2297.

Garcia-Rill E, Saper CB, Rye DB, Kofler M, Nonnekes J, Lozano A, Valls-Solé J, Hallett M. Focus on the pedunculopontine nucleus. Consensus review from the May 2018 brainstem society meeting in Washington, DC, USA. Clin Neurophysiol. 2019 Jun;130(6):925-940.

González-Rueda A, Jensen K, Noormandipour M, de Malmazet D, Wilson J, Ciabatti E, Kim J, Williams E, Poort J, Hennequin G, Tripodi M. Kinetic features dictate sensorimotor alignment in the superior colliculus. Nature. 2024 Jul;631(8020):378-385.

Gordon, J., Maselli, A., Lancia, G. L., Thiery, T., Cisek, P., & Pezzulo, G. (2021). The road towards understanding embodied decisions. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 131, 722-736.

Grätsch, S., 2018. Descending control of locomotion in the lamprey (Doctoral dissertation, Universität zu Köln).

Guillamón-Vivancos, T., Favaloro, F., Dori, F. and López-Bendito, G., 2024. The superior colliculus: New insights into an evolutionarily ancient structure. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 89, p.102926

Hadjas, L.C., Kollman, G.J., Linderhof, L., Xia, M., Mansur, S., Saint-Pierre, M., Lim, B.K., Lee, E.B., Cicchetti, F., Awatramani, R. and Hollon, N.G., 2025. Parkinson’s Disease-vulnerable and-resilient dopamine neurons display opposite responses to excitatory input. BioRxiv.

Hormigo S, Zhou J, Chabbert D, Sajid S, Busel N, Castro-Alamancos M. Zona incerta distributes a broad movement signal that modulates behavior. Elife. 2023 Dec 4;12:RP89366.

Horwitz GD, Newsome WT. Separate signals for target selection and movement specification in the superior colliculus. Science. 1999 May 14;284(5417):1158-61.

Huang, M., Li, D., Cheng, X., Pei, Q., Xie, Z., Gu, H., Zhang, X., Chen, Z., Liu, A., Wang, Y. and Sun, F., 2021. The tectonigral pathway regulates appetitive locomotion in predatory hunting in mice. Nature communications, 12(1), p.4409.

Jang EV, Ramirez-Vizcarrondo C, Aizenman CD, Khakhalin AS. Emergence of Selectivity to Looming Stimuli in a Spiking Network Model of the Optic Tectum. Front Neural Circuits. 2016 Nov 24;10:95.

Jiang H, Stein BE, McHaffie JG. Opposing basal ganglia processes shape midbrain visuomotor activity bilaterally. Nature. 2003 Jun 26;423(6943):982-6.

Kacelnik A, Vasconcelos M, Monteiro T, Aw J. 2011. Darwin’s ‘tug-of-war’ vs. starlings’ ‘horse-racing’: how adaptations for sequential encounters drive simultaneous choice. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 65, 547-558.

Kardamakis AA, Pérez-Fernández J, Grillner S. Spatiotemporal interplay between multisensory excitation and recruited inhibition in the lamprey optic tectum. Elife. 2016 Sep 16;5:e16472.

Khilkevich A, Lohse M, Low R, Orsolic I, Bozic T, Windmill P, Mrsic-Flogel TD. Brain-wide dynamics linking sensation to action during decision-making. Nature. 2024 Oct;634(8035):890-900.

Kohashi T, Nakata N, Oda Y. Effective sensory modality activating an escape triggering neuron switches during early development in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2012 Apr 25;32(17):5810-20.

Koyama M, Minale F, Shum J, Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Fetcho JR. A circuit motif in the zebrafish hindbrain for a two alternative behavioral choice to turn left or right. Elife. 2016 Aug 9;5:e16808.

Krauzlis RJ, Lovejoy LP, Zénon A. Superior colliculus and visual spatial attention. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2013 Jul 8;36:165-82. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062012-170249. Epub 2013 May 15.

Larbi MC, Messa G, Jalal H, Koutsikou S. An early midbrain sensorimotor pathway is involved in the timely initiation and direction of swimming in the hatchling Xenopus laevis tadpole. Front Neural Circuits. 2022 Dec 21;16:1027831.

Lee J, Sabatini BL. Striatal indirect pathway mediates exploration via collicular competition. Nature. 2021 Nov;599(7886):645-649.

Leiras, R., Cregg, J.M. and Kiehn, O., 2022. Brainstem circuits for locomotion. Annual review of neuroscience, 45(1), pp.63-85.

Liu X, Huang H, Snutch TP, Cao P, Wang L, Wang F. The Superior Colliculus: Cell Types, Connectivity, and Behavior. Neurosci Bull. 2022 Dec;38(12):1519-1540.

Liu Z, Ciarleglio CM, Hamodi AS, Aizenman CD, Pratt KG. A population of gap junction-coupled neurons drives recurrent network activity in a developing visual circuit. J Neurophysiol. 2016 Mar;115(3):1477-86.

Lu, W. and Wan, X., 2025. Closing The Loop: A Dynamic Neural Network Model Integrating Decision making and Metacognition. bioRxiv, pp.2025-03.

Mahajan NR, Mysore SP. Donut-like organization of inhibition underlies categorical neural responses in the midbrain. Nat Commun. 2022 Mar 30;13(1):1680.

Marín G, Salas C, Sentis E, Rojas X, Letelier JC, Mpodozis J. A cholinergic gating mechanism controlled by competitive interactions in the optic tectum of the pigeon. J Neurosci. 2007 Jul 25;27(30):8112-21.

Masullo L, Mariotti L, Alexandre N, Freire-Pritchett P, Boulanger J, Tripodi M. Genetically Defined Functional Modules for Spatial Orienting in the Mouse Superior Colliculus. Curr Biol. 2019 Sep 9;29(17):2892-2904.e8

Melleu FF, Canteras NS. Pathways from the Superior Colliculus to the Basal Ganglia. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2024;22(9):1431-1453.

Mena-Segovia J, Micklem BR, Nair-Roberts RG, Ungless MA, Bolam JP. GABAergic neuron distribution in the pedunculopontine nucleus defines functional subterritories. J Comp Neurol. 2009 Aug 1;515(4):397-408.

Morgenstern NA, Esposito MS. The Basal Ganglia and Mesencephalic Locomotor Region Connectivity Matrix. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2024;22(9):1454-1472.

Mysore SP, Kothari NB. Mechanisms of competitive selection: A canonical neural circuit framework. Elife. 2020 May 20;9:e51473.

Patton, P., Windsor, S. and Coombs, S., 2010. Active wall following by Mexican blind cavefish (Astyanax mexicanus). Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 196, pp.853-867.

Perez-Fernandez, J., Kardamakis, A.A., Suzuki, D.G., Robertson, B. and Grillner, S., 2017. Direct dopaminergic projections from the SNc modulate visuomotor transformation in the lamprey tectum. Neuron, 96(4), pp.910-924.

Piet AT, El Hady A, Brody CD. Rats adopt the optimal timescale for evidence integration in a dynamic environment. Nat Commun. 2018 Oct 15;9(1):4265.

Poisson, C.L., Wolff, A.R., Prohofsky, J., Herubin, C., Blake, M. and Saunders, B.T., 2024. Superior colliculus projections drive dopamine neuron activity and movement but not value. bioRxiv, pp.2024-10.

Pradel K, Drwiȩga G, Błasiak T. Superior Colliculus Controls the Activity of the Rostromedial Tegmental Nuclei in an Asymmetrical Manner. J Neurosci. 2021 May 5;41(18):4006-4022.

Ratcliff, R., 1978. A theory of memory retrieval. Psychological review, 85(2), p.59.

Ricci, A., Rubino, E., Serra, G.P. and Wallén-Mackenzie, Å., 2024. Concerning neuromodulation as treatment of neurological and neuropsychiatric disorder: Insights gained from selective targeting of the subthalamic nucleus, para-subthalamic nucleus and zona incerta in rodents. Neuropharmacology, 256, p.110003.

Rimmer, N., 2020. The physiological and functional characterisation of the subpallial dopaminergic neurons in larval zebrafish (Doctoral dissertation, University of Leicester).

Ryczko, D., Grätsch, S., Auclair, F., Dubé, C., Bergeron, S., Alpert, M.H., Cone, J.J., Roitman, M.F., Alford, S. and Dubuc, R., 2013. Forebrain dopamine neurons project down to a brainstem region controlling locomotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(34), pp.E3235-E3242

Ryczko D, Auclair F, Cabelguen JM, Dubuc R. The mesencephalic locomotor region sends a bilateral glutamatergic drive to hindbrain reticulospinal neurons in a tetrapod. J Comp Neurol. 2016 May 1;524(7):1361-83.

Ryczko, D., Cone, J.J., Alpert, M.H., Goetz, L., Auclair, F., Dubé, C., Parent, M., Roitman, M.F., Alford, S. and Dubuc, R., 2016. A descending dopamine pathway conserved from basal vertebrates to mammals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(17), pp.E2440-E2449.

Ryczko, D. and Dubuc, R., 2017. Dopamine and the brainstem locomotor networks: from lamprey to human. Frontiers in neuroscience, 11, p.295.

Ryczko, D. and Dubuc, R., 2023. Dopamine control of downstream motor centers. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 83, p.102785.

Salas, C., 2016. The central nervous system of agnathans: an ontogenetic and phylogenetic study of encephalization and brain organization in lampreys and hagfishes.

Schall JD, Purcell BA, Heitz RP, Logan GD, Palmeri TJ. Neural mechanisms of saccade target selection: gated accumulator model of the visual-motor cascade. Eur J Neurosci. 2011 Jun;33(11):1991-2002.

Schryver, H.M., 2021. Functional Properties of Inhibitory Neurons in the Avian Midbrain Attention Network (Doctoral dissertation, Johns Hopkins University).

Seiler, J.L., Zhuang, X., Nelson, A.B. and Lerner, T.N., 2024. Dopamine across timescales and cell types: Relevance for phenotypes in Parkinson’s disease progression. Experimental Neurology, 374, p.114693.

Shen B, Louie K, Glimcher P. Flexible control of representational dynamics in a disinhibition-based model of decision-making. Elife. 2023 Jun 1;12:e82426.

Simonnet J, Nassar M, Stella F, Cohen I, Mathon B, Boccara CN, Miles R, Fricker D. Activity dependent feedback inhibition may maintain head direction signals in mouse presubiculum. Nat Commun. 2017 Jul 20;8:16032.

Suryanarayana, S. M., Perez-Fernandez, J., Robertson, B., & Grillner, S. (2021). Olfaction in lamprey pallium revisited—dual projections of mitral and tufted cells. Cell Reports, 34(1).

Suryanarayana SM, Pérez-Fernández J, Robertson B, Grillner S. The Lamprey Forebrain – Evolutionary Implications. Brain Behav Evol. 2022;96(4-6):318-333. doi: 10.1159/000517492. Epub 2021 Jun 30.

Thomas A, Yang W, Wang C, Tipparaju SL, Chen G, Sullivan B, Swiekatowski K, Tatam M, Gerfen C, Li N. Superior colliculus bidirectionally modulates choice activity in frontal cortex. Nat Commun. 2023 Nov 14;14(1):7358.

Thura D, Beauregard-Racine J, Fradet CW, Cisek P. Decision making by urgency gating: theory and experimental support. J Neurophysiol. 2012 Dec;108(11):2912-30.

Tubert C, Galtieri D, Surmeier DJ. The pedunclopontine nucleus and Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2019 Aug;128:3-8.

Uribe-Arias A, Rozenblat R, Vinepinsky E, Marachlian E, Kulkarni A, Zada D, Privat M, Topsakalian D, Charpy S, Candat V, Nourin S, Appelbaum L, Sumbre G. Radial astrocyte synchronization modulates the visual system during behavioral-state transitions. Neuron. 2023 Dec 20;111(24):4040-4057.e6.

Usher, M. and McClelland, J.L., 2001. The time course of perceptual choice: the leaky, competing accumulator model. Psychological review, 108(3), p.550.

Verdonck, S., Loossens, T. and Philiastides, M.G., 2021. The Leaky Integrating Threshold and its impact on evidence accumulation models of choice response time (RT). Psychological Review, 128(2), p.203.

Vickers, D., 1970. Evidence for an accumulator model of psychophysical discrimination. Ergonomics, 13(1), pp.37-58.

Volkmann, K., Chen, Y.Y., Harris, M.P., Wullimann, M.F. and Köster, R.W., 2010. The zebrafish cerebellar upper rhombic lip generates tegmental hindbrain nuclei by long‐distance migration in an evolutionary conserved manner. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 518(14), pp.2794-2817.

Wei W, Rubin JE, Wang XJ. Role of the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia in perceptual decision making. J Neurosci. 2015 Mar 4;35(9):4052-64.

Westphal, R.E. and O’Malley, D.M., 2013. Fusion of locomotor maneuvers, and improving sensory capabilities, give rise to the flexible homing strikes of juvenile zebrafish. Frontiers in neural circuits, 7, p.108.

Wheatcroft, T.G., 2022. Projection-specific anatomy, physiology and behaviour in the mouse superior colliculus (Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London)).

Wolf AB, Lintz MJ, Costabile JD, Thompson JA, Stubblefield EA, Felsen G. An integrative role for the superior colliculus in selecting targets for movements. J Neurophysiol. 2015 Oct;114(4):2118-31.

Wu, Q. and Zhang, Y., 2023. Neural circuit mechanisms involved in animals’ detection of and response to visual threats. Neuroscience Bulletin, 39(6), pp.994-1008.

Xie Z, Wang M, Liu Z, Shang C, Zhang C, Sun L, Gu H, Ran G, Pei Q, Ma Q, Huang M, Zhang J, Lin R, Zhou Y, Zhang J, Zhao M, Luo M, Wu Q, Cao P, Wang X. Transcriptomic encoding of sensorimotor transformation in the midbrain. Elife. 2021 Jul 28;10:e69825.

Zahler, S.H., Taylor, D.E., Wong, J.Y., Adams, J.M. and Feinberg, E.H., 2021. Superior colliculus drives stimulus-evoked directionally biased saccades and attempted head movements in head-fixed mice. Elife, 10, p.e73081.

Zylbertal A, Bianco IH. Recurrent network interactions explain tectal response variability and experience-dependent behavior. Elife. 2023 Mar 21;12:e78381.